Our blog is moving...

but check out the exciting features in the adidas Running app that will help you start running!

OPEN ADIDAS RUNNING

CHOOSE YOUR PLAN

JOIN EVENTS OR RUN ALONE WITH ADIDAS RUNNING

Set goals, check in for events, earn rewards, and have more fun on your runs with these features:

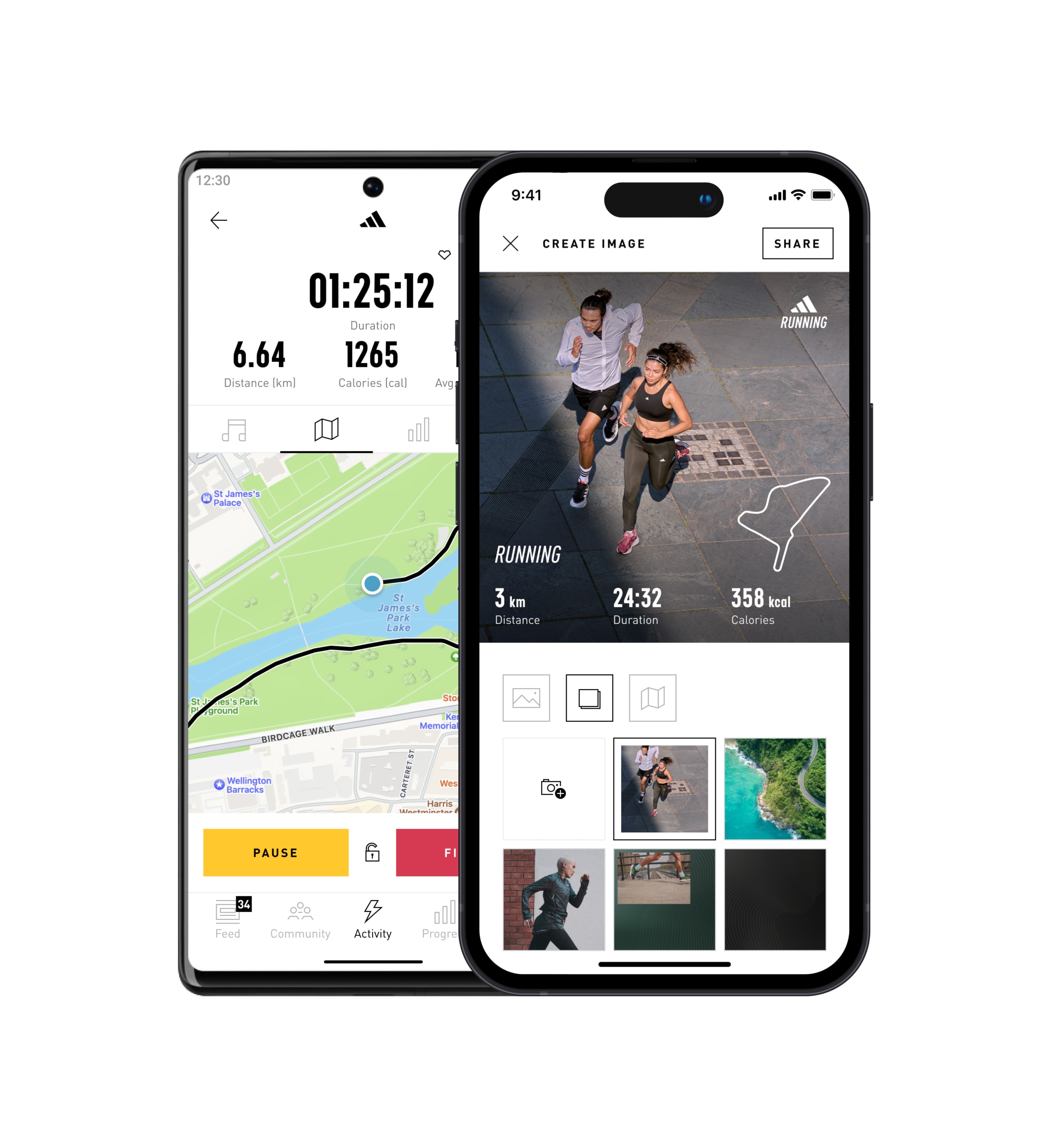

Voice Coach

GPS Tracking

Leaderboard

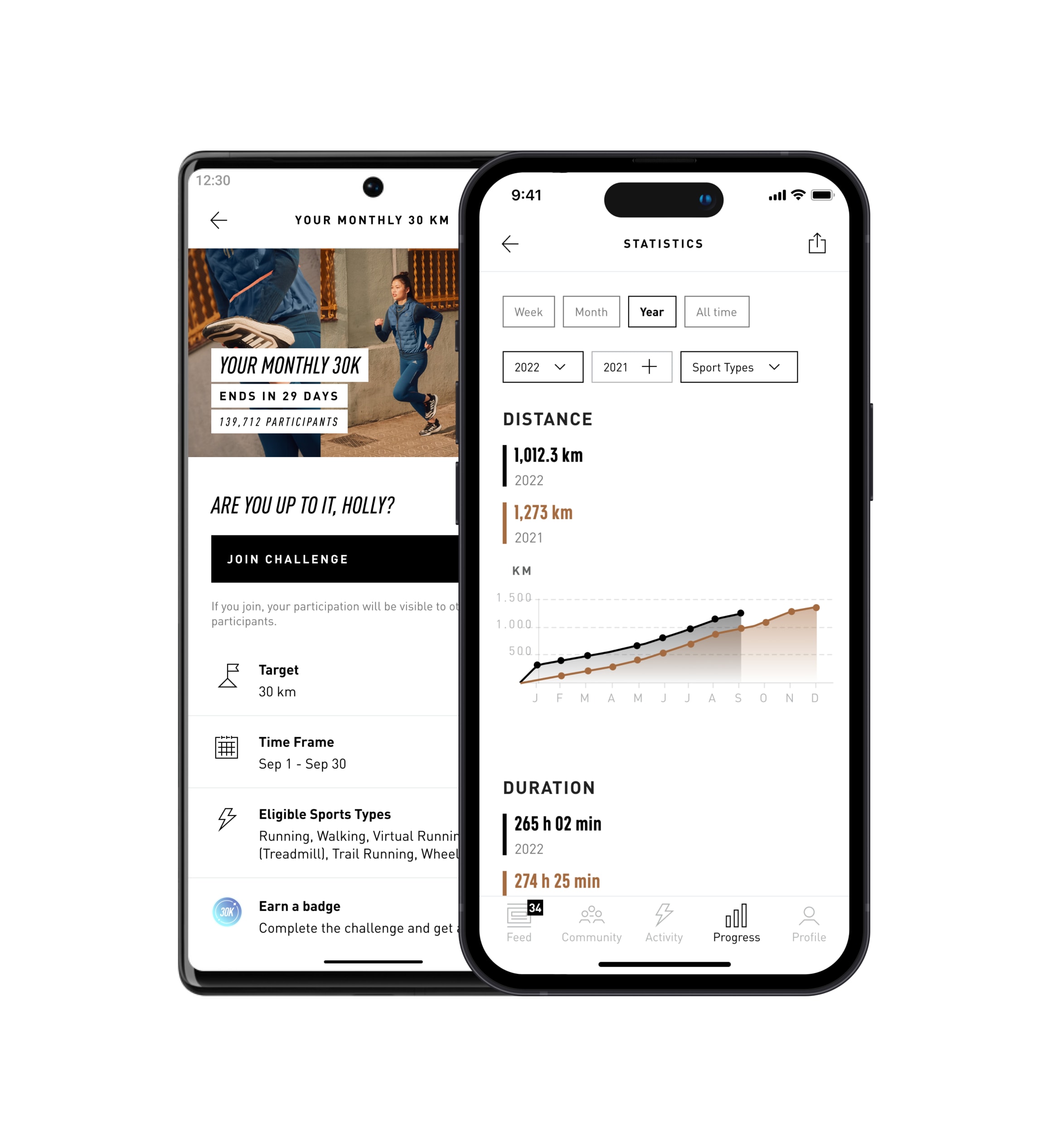

Running Stats

Challenges

Training Plans